Telescope Sites I: Latitude, Pointing, and Sky

Introduction/Generalities

In an intro to astronomy class (or general outreach), The sky available at a site is often naively approximated as 2π steradians (or rather 180 degrees from horizon to horizon). Certainly an amateur scope can reach 0 (or for that matter negative) elevation, and for small sizes, amateur and professional equipment overlap. But larger ones cannot, and lower angles become increasingly difficult (or impossible for designs like HET, SALT, and zenith telescopes), and defacto limits from airmass often minimize the utility of low angles.

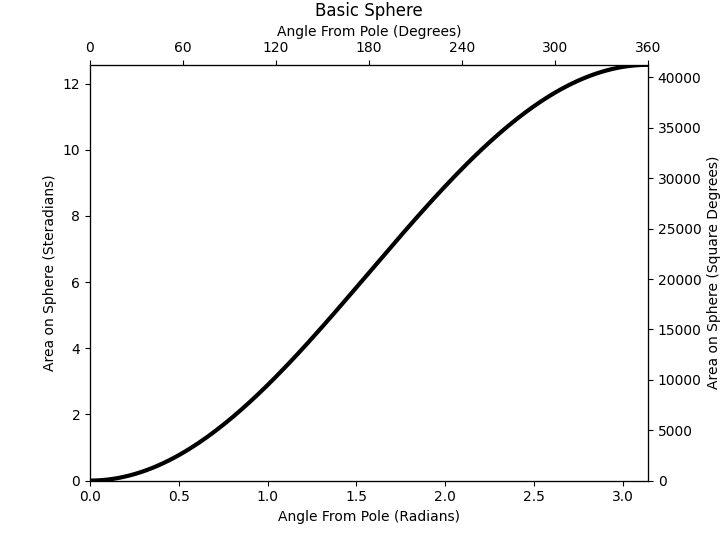

Conveniently, the angular area that can be seen at a given site, can be found with a bit of integration: \(\int\int sin(\theta) d\theta d\phi\)

Integrating with respect to angle from the pole…

The full sphere is 4π (~12.566) steradians, or ~40253 square degrees.

Location for point obs

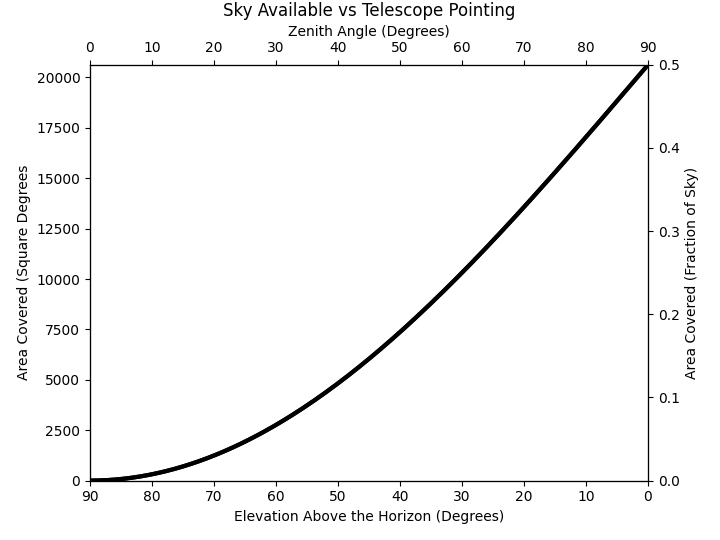

Sadly, the right half of that graph is unavailable for any ground based telescope. In a perfect world (ie: the telescope is mounted on a spherical cow in a vacuum, and can point to the horizon), you can get the aforementioned 2π steradians. For a real telescope, a good approximation is 60 degrees from zenith/30 degrees elevation (ie: an airmass of 2).

This gives you π steradians (1/4 of the sky). If you can get a bit lower (most telescopes can), you can get a bit more area, but this gets offset by other things. e.g.: telescopes take a finite amount of time to point, and exoposures are also not instantaneous (nominal values tend to skew to 5 minutes for each repointing at professional observatories, though once you get at or below ~4 m class, they can be much faster in practice).

For the remainder of this, I will be using square degrees for area on the sky, minimum elevation above the horizon (in degrees) for the telescope pointing limits, and latitude of the observatory (in degrees), since those are more common/widely understood. (steradian is just a fancy way of saying radian², and the conversion works like that high school formula of 180/π. You just apply it twice.)

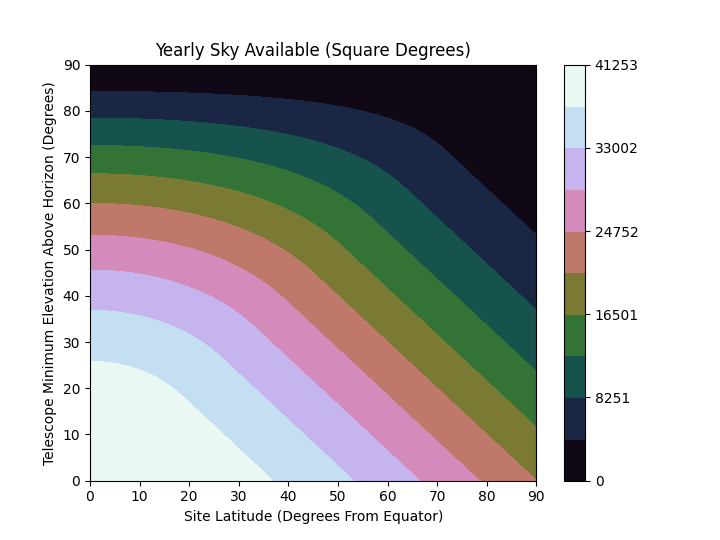

Availability over the course of the year

Most telescopes can see most of the sky (at least occasionally). In reality, objects at the edges can be made impractical by night length, weather, or if one is sufficiently unlucky the moon.

Handwaving per-night stuff, and just considering the site as a circular patch rotating around a sphere, the yearly coverage is a more or less ring shaped extending between latitude+pointing and latitude-pointing. If the pointing angle is larger than the latitude, you can see “past” the pole, and at least in principle some objects are always observable.

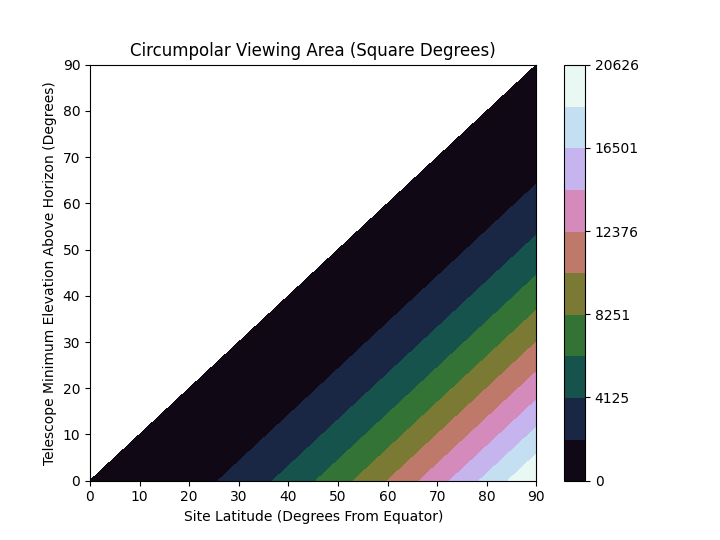

Circumpolar stars (and galaxies) don’t actually exist

To start with, let’s look at how large the “continuous viewing zone” actually is for any given telescope

If a site is unusually high latitude and/or points at unusually low angles there are some circumpolar objects worth observing, but this is very much the exception. The large telescopes (typ min elevation ~30 degrees), are typically located within 35 degrees of the equator. A sample of optical observatories large enough to cover most latitudes and longitudes:

| Site | Latitude (deg) | Longitude (deg) | Altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mauna Kea (Keck) | +19.8243 | -155.4742 | 4145 |

| Kitt Peak (WIYN) | +31.9575 | -111.6008 | 2096 |

| Cerro Tololo (Victor Blanco) | -33.1697 | -70.8064 | 2207 |

| Las Campanas (Magellan) | -29.0150 | -70.6917 | 2516 |

| Paranal (VLT) | -24.627222 | -70.404167 | 2635 |

| Calar Alto (3.5 m) | +37.2236 | +2.5461 | 2168 |

| Sutherland (SALT, SuperWASP) | -32.3783 | +18.4776 | 1798 |

| Special Astrophysical Observatory (БТА-6) | +43.6468 | +41.4405 | 2070 |

| Xinglong Station (LAMOST) | +40.395761 | +117.575861 | 960 |

| Siding Spring (AAT) | -31.2703 | +149.0669 | 1134 |

(Not shown: SPT, BICEP, and the like, which are at 90 degrees south, and potentially have large continous viewing areas. But they are not used for the sort of transient searches that would make this most appealing. And the long periods of daylight and twilight would hinder optical instruments…)

A dedicated low angle telescope could plausibly have 5-10% of the sky be circumpolar at those latitudes, but that’s not a lot. And with the actual pointing limits of actual telescopes, it’s possible that there’s a hole around the pole where no observations at all are possible.

Conclusions

Location isn’t that important in terms of latitude, as most low-mid ones are good. Pointing matters, but “good enough” is often easily achievable. The idea of a telescope dedicated to a small patch of sky near one of the celestial poles is more mirage than reality. Consider a low latitude band like Stripe 82 or the ecliptic?