Interstellar Spaceflight: Rocketry Limitations and Ease of Navigation

Interstellar spaceflight is a fun field to speculate on, provided it’s somewhat grounded in reality. I will not being doing any EM Drive, Alcubierre Drive, etc shenanigans, or even focusing on the decidedly plausible lightsails/laser sails. (Though the last ones are quite cool!). Rather, I’ll be focusing on why trajectories are easy, and even if you somehow have a photon rocket, you’re quite limited by relativity. There’s no overall conclusion on what is good/bad, just an attempt at clarification.

Stars are moving, but it barely matters

Stellar motions are at most a few hundred km/s. This is decidedly important for tracing the trajectories of interstellar comets, or what the 5 spacecraft leaving the solar system will eventually encounter, but otherwise is only a minor correction factor.

Now, how fast are you planning on going? Yes, waiting tens of thousands to a few million years can get you noticeably shorter flights. But how does that compare to your flight time? Normally you want at most a few hundred years, and a few decades (or less!) makes the missions vastly more plausible and tractible. This implies speeds on the order of 1%-30% the speed of light (possibly faster), in which case you are moving at least an order of magnitude faster than the stars. Sure, you can’t point at where they are now, but aiming is not a difficult problem.

You’ll also occasionally see weird descriptions of the precision required that that make it sound impossible. I’m unsure where these come from, given that spacecraft have been doing mid-course corrections since the very start of the space age.

Gravitational slingshots are for comets, not you

The above speeds are rather large compared to solar system escape velocity, and if you’re starting from more than a few solar radii, relative stellar speeds may be larger! If you’re doing just over 1% c (3000 km/s), suddenly the 618 km/s of solar escape from the sun’s photosphere or 59.5 km/s of planetary escape from Jupiter’s cloud-tops don’t seem so extreme. You just can’t bend an orbit that much at those speeds.

(There’s probably a case to be made for doing a more detailed analysis on how much you can gain, but I’m reminded that “The Starflight Handbook” specifically mentioned close binaries of white dwarfs and neutron stars for these sorts of things.)

Oberth helps, but only for interplanetary missions

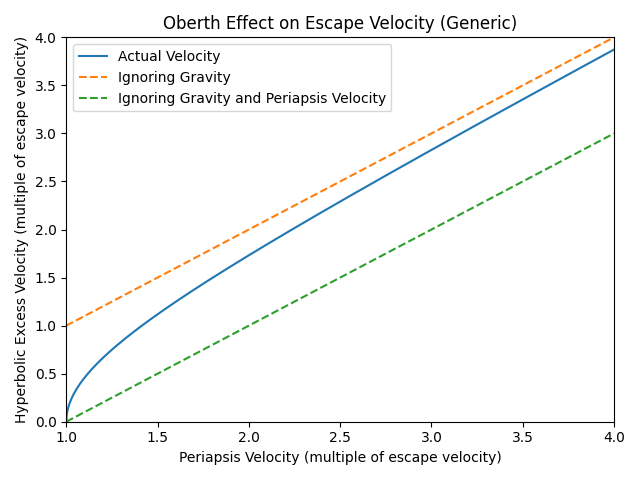

A key equation is: \(V_{esc}^2 + V_{hyp}^2 = V_{periapsis}^2\). David Hop goes into the value of this in a planetary context, but as our periapsis and hyperbolic excess velocities becomes much greater than escape velocity, it becomes rather minor. This tends to be clearer with graphs:

This is a generic case (escape velocity = 1). Initially, larger burns at periapsis result in large gains (compared with a flat space case), but the ultimate boost available has a finite upper limit (escape velocity). Once one is looking at Δvs of a few times that, the gains do very little for travel time.

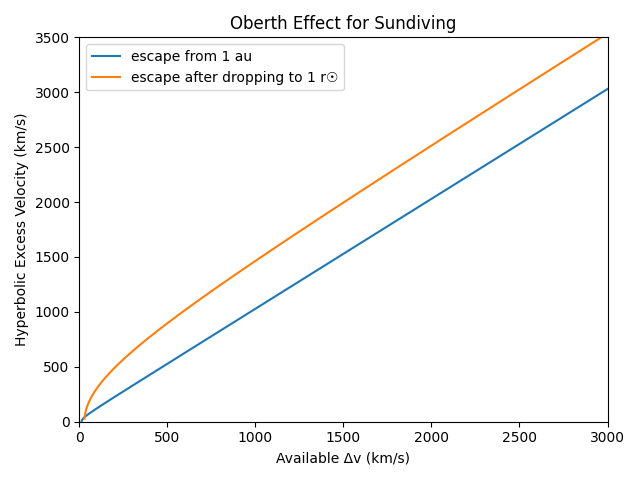

To see how this plays out, let’s look at the actual sun. Two cases: 1) escaping from 1 au, and 2) burning to drop your perihelion to skimming the photosphere (~1 \(R_{\odot}\)), and then using your remaining Δv to burn to escape:

For extremely low Δv, burning to escape instead of dropping your orbit to be sun-skimming first is better (because it’s cheaper), but you quickly get into a regime where there are large (and technically ever increasing) gains. While in this case the numbers eventually reach over 500 km/s, by this time you’re travelling at over 0.01 c (~3000 km/s for the earth case, ~3500 km/s for the sun skimmer). For craft with Δv ~ 0.02 c, the difference is under 10%, and will continue to shrink in relative terms for faster craft. (In absolute terms, it eventually grows to a limit of ~560 km/s. This less than 618 km/s because of needing to deorbit from a finite altitude; falling from infinity would allow for the full gain.)

It’s rather striking that the finite sizes of planets and stars result in a finite amount of velocity available to you with this maneuver. And since that amount is ≤ \(V_{esc}\), which is in turn much less than what you want for interstellar travel, Oberth fades into the details. Design considerations that I’m outright ignoring (where/how to construct craft, burn times, etc) are likely more important. Or maybe one should just give up on rockets and focus on solar/laser sails?

Relativity doesn’t matter at the low end of speeds

It’s worth playing around with Lorentz factors a bit to make this clear. But for some quick heuristics: You need to be doing ~0.42 c for 10% effects, ~0.14 c for 1% effects, and ~0.045 c for 0.1% effects. Rough Newtonian approximations breaking down only as you get past 50% of the speed of light may be surprising, but it’s how the math shakes out. So all those 1%-20% c proposals for travel to nearby stars only need to consider relativity for design details!

The Rocket Equation will make you suffer even when you don’t have to deal with SR/GR

It’s an exponential equation, see. The rule of thumb is that you can’t get much beyond a mass ratio of 20, or a Δv beyond about 3x your exhaust velocity. At least for 1-2 stages of chemical propulsion. This breaks down pretty dramatically for some systems (eg: xenon is very dense, and many different nuclear systems have poor mass ratios), but remains useful as a starting point. Unless your exaust velocity is within a factor of a few of your target Δv, you’re going to need propellant in quantities that are at best impractical and at worst unphysical. So expect a need for ones at least a few percent of c. Or sidestep it with solar/laser sails.

As always, that one ISS astronaut’s essay is relevant (even if it’s focused on issues that are much nearer to Earth).

If you have a photon rocket, Einstein will still limit you

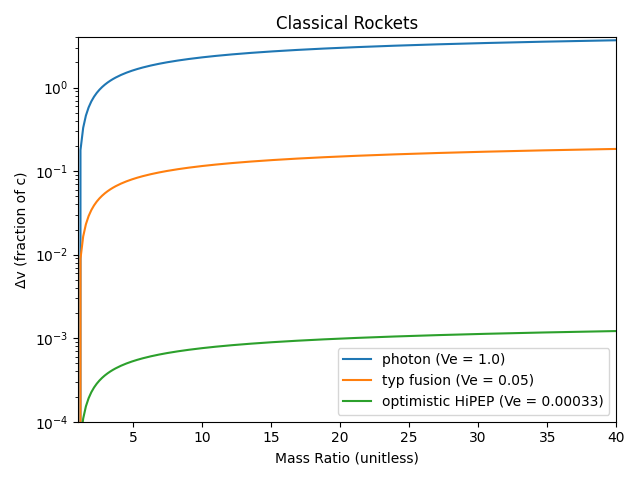

It’s easiest to show how this is a problem by using the regular and relativistic rocket equations, and graphing out the performance of a few different example craft.

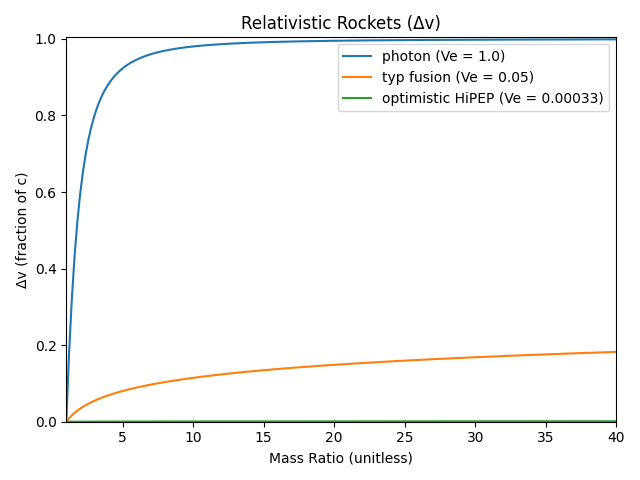

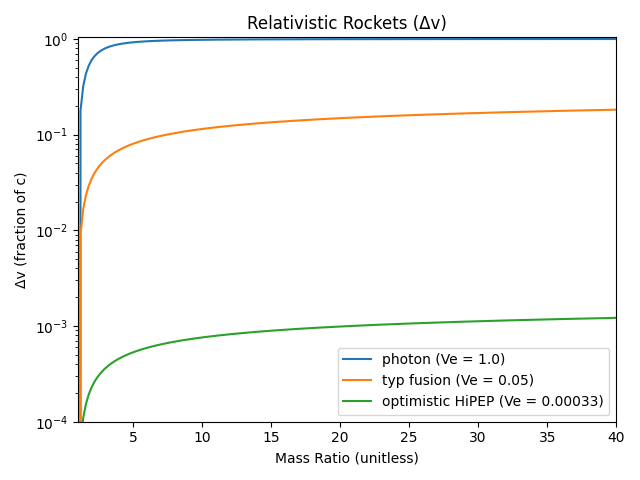

For the purposes of this comparison, I’m looking at an ideal photon rocket (\(V_e = c\)), a more or less typical fusion rocket (\(V_e = 0.05 c\), and I don’t care if it’s more like Daedalus or Orion), and an ion rocket using something like the higher end tests of HiPEP (\(V_e\) ~ 100 km/s, or \(I_{sp}\) ~ 10,000 sec).

I’m starting with the rocket equation that we all know and hate. The large \(I_{sp}\) range differentiates the 3 kinds of rockets pretty strongly. For this and the following graphs, I’m looking at mass ratios of up to 40, which effectively includes most multistage designs. Since this is using classical mechanics, the photon rocket ends up getting to ~3.8 c.

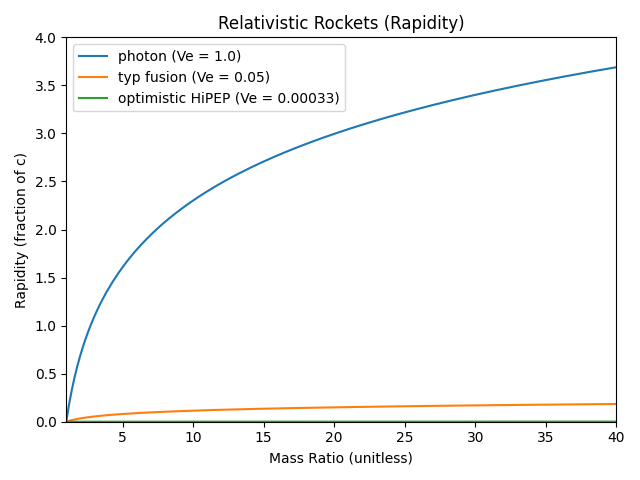

Rapidity is a relativistic quantity that basically acts like classical Δv, so you get a consistent value that avoids how a rocket that could accelerate to 0.9 c and decellerate back to 0, actually can’t get up to 1.8 c by burning all of its fuel.

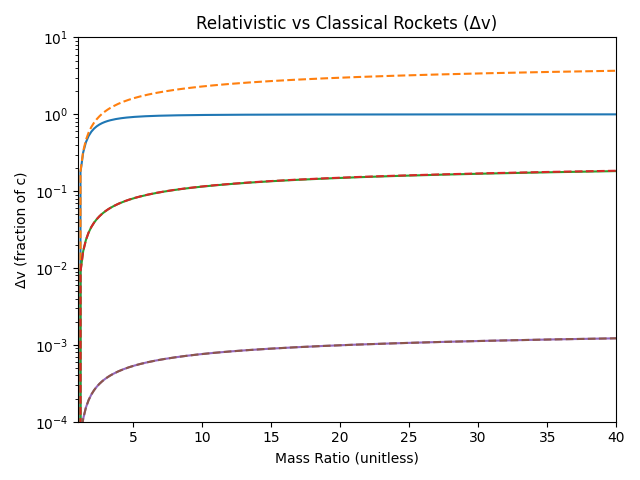

When the full relativistic equation is used, the photon rocket suffers greatly, but the effects on the others are much more subtle. This is unsurprising, since neither ever gets to γ > 1.1. Δv is showin in both linear and log scales.

Finally, a comparison (1-way) Δv in the classical (dashed) and relativistic (solid) regimes. Rather strikingly, they overlap for everything except the photon rocket (mainly because it’s the only one that gets up past 0.2 c). Of course, if one doesn’t burn all their fuel trying to get that last few percent of c, they accelerate and decelerate many times to close to it.