Optimizing Stage Performance Revisted

Previously, I developed staging models for KSP, and it turns out you can automatically get the amount of payload possible and tankage required for any engine/mission combination. But part of this is how tanks (usually) have a fixed mass ratio of 9.

In the Realism Overhaul for KSP, you have procedural tanks where the mass is constant with volume, but propellant density, tank mass, and usable volume vary with tank type and propellant choice.

In Juno: New Origins, you have procedural tanks that you can define the size/shape of in a more or less arbitrary manner. This also means that your mass ratio is not constant, and depends on tank design. Can we still usefully optimize things here? With some assumptions, Yes!

(Re)Derivation for Surface Area and Volume

\[TMR = \frac{F}{m_1}\]\(m_1 = m_{Engine} + σ \cdot A + ρ \cdot V + m_{Payload}\) (tanks have a surface area with a consistent density, and internal volume that can be filled with propellants)

\[m_2 = m_{Engine} + σ \cdot A + m_{Payload}\] \[e^\frac{Δv}{I_{sp} \cdot g_0} \cdot m_2 = m_1\]Substituting in the values for the initial and final masses: \(e^\frac{Δv}{I_{sp} \cdot g_0} \cdot \left(\frac{F}{TMR} - ρ \cdot V\right) = \frac{F}{TMR}\)

Solving for propellant mass and/or Volume: \(ρ \cdot V = \frac{F}{TMR}\left(1 - exp(-\frac{Δv}{I_{sp} \cdot g_0})\right)\) \(V = \frac{F}{ρ \cdot TMR}\left(1 - exp(-\frac{Δv}{I_{sp} \cdot g_0})\right)\)

And payload mass from TMR: \(m_{Payload} = \frac{F}{TMR} - \left(m_{Engine} + σ \cdot A + ρ \cdot V\right)\)

So as long as we choose tanks where the surface area is consistent function of volume, this remains doable. And even if we don’t, there’s an intriguing generalization: the equations give us propellant mass required, and the “payload” can be thought of as all other mass (empty tanks, control systems, etc, as well as actual payload).

But what sort of tankage?

In lots of games, tanks are assumed to have an arbitrarily thin skin, so as to make surface area and volume calculations simple. Though note that they also often make shape assumptions.

Juno: New Origins

The skin of the tanks always has σ = 12.5 kg/m². For ρ, the value will depend on the propellant choice and the (hidden) tank/propellant properties (both density and how much the tanks can be filled. See the table for details). eg: 561 kg/m³ for kerolox, 176 kg/m³ for hydrolox, and 434.5 kg/m³ for methalox.

In principle, the optimal shape for a cylinder (in terms of minimizing surface area/maximizing volume) has the same diameter and height (h = 2r). In reality, aerodynamic requirements can mess this up (so perhaps you want h = 6r or more). Also more subtlely, taking a tank that has these dimensions and expanding it in either radius or height will improve the mass ratio. It’s just not as much of a gain as it could be if both dimensions are expanded in a balanced manner. Nonetheless:

\[A = 2(πr^2) + 2πrh = 6πr^2\] \[V = πr^2h = 2πr^3\]Which we can plug into the previous equations to get tank radius in terms of mission goals. Sort of. In reality, JNO doesn’t quite model those cylinders as cylinders, so they have slightly less surface area and volume than you’d expect. (more on this later)

\[2πr^3 = \frac{F}{ρ \cdot TMR}\left(1 - exp(-\frac{Δv}{I_{sp} \cdot g_0})\right)\] \[r = \sqrt[3]{\frac{F}{2πρ \cdot TMR}\left(1 - exp(-\frac{Δv}{I_{sp} \cdot g_0})\right)}\]And finally maximum payload for this craft:

\[m_{Payload} = \frac{F}{TMR} - \left(m_{Engine} + σ6πr^2 + ρ2πr^3\right)\]If one is interested in payload fraction (for eg: comparing relative efficiency across very different designs):

\[f_{Payload} = 1 - \frac{TMR}{F}\left(m_{Engine} + σ6πr^2 + ρ2πr^3\right)\]Cylinders or Polygons?

Actual JNO tanks are 24-sided polygons inscribed in the circles of the radii you’d expect/see in the build screen, instead of cylinders. For tanks made out of these sorts of n-sided prisms with a nominal radius of r:

Side length \(= 2r \cdot sin(π/n)\)

Perimeter \(= 2nr \cdot sin(π/n)\)

Area \(= n (0.5)(2r \cdot sin(π/n))(r \cdot cos(π/n)) = nr^2 \cdot sin(π/n)cos(π/n) = \frac{n}{2}r^2 \cdot sin(2π/n)\)

Total surface area \(= nr^2 \cdot sin(2π/n) + 2nrh \cdot sin(π/n)\)

Total volume \(= nr^2h \cdot sin(π/n) cos(π/n) = \frac{n}{2}r^2h \cdot sin(2π/n)\)

For maximum annoyance, these polygons are from the default “rounding” of the corners. With that turned off, the bases are rectangles that extend the full disance specified by the length/width. (Though like cylinders, the optimal size is the diameter and height being the same. Or, are cube.)

Polygonal Properties

As rectangular prisms (ie: none of JNO’s corner rounding), the optimal shape is clearly a cube (or “diameter” and height are the same). It takes a bit of math, but the same ratio holds for cylinders. For an inscribed polygon, you end up wanting a slightly shorter(!) configuration: \(h = 2r \cdot cos(π/n)\) (Though for n=24, this is over 99% of the height of the previous cases, so eh).

Incidentally, for cubes, optimal cylinders, and spheres, the surface area to volume ratio ends up being 3/r (or 6/d). In part because of how they have area scaling with r² but volume with r³…

For completeness, this means that:

\[V = 2πr^3cos(π/n)\] \[A = 2πr^2 + 4πr^2cos(π/n) = 2πr^2(1+2\cdot cos(π/n))\]And finally in terms of rocket properties:

\[r = \sqrt[3]{\frac{F}{2πρ \cdot cos(π/n) \cdot TMR}\left(1 - exp(-\frac{Δv}{I_{sp} \cdot g_0})\right)}\] \[m_{Payload} = \frac{F}{TMR} - \left(m_{Engine} + σ2πr^2(1+2\cdot cos(π/n)) + ρ2πr^3cos(π/n)\right)\] \[f_{Payload} = 1 - \frac{TMR}{F} \left(m_{Engine} + σ2πr^2(1+2\cdot cos(π/n)) + ρ2πr^3cos(π/n)\right)\]Radius vs Height

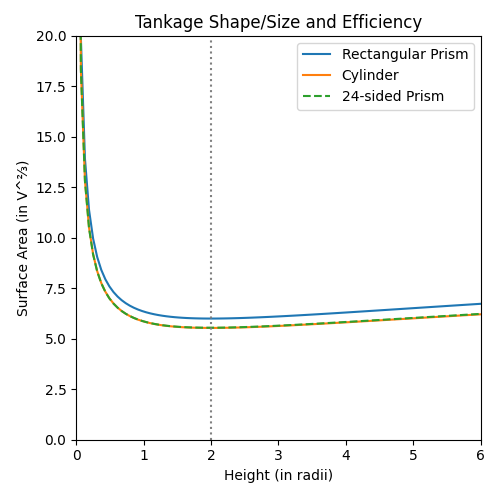

But while the above are optimal in terms of mass ratios, we may be constrained by other features. Most notably, wanting a relatively tall and thin rocket to minimize drag. How much does that matter?

There’s a few different ways to try to parameterize it. I went with defining the height in terms of either the diameter or radius: \(h = k \cdot r\), where \(k\) is the height in radii (or diameters).

This lets you find a radius in terms of the volume and radius to height ratio, and then a surface area in terms of volume and the radius to height ratio.

For a cylinder: \(S = 2 π^{1/3} V^{2/3} (k^{-2/3}+K^{1/3})\)

For a rectangular prism: \(S = 2^{5/3} V^{2/3} (k^{-2/3}+k^{1/3})\) or if using diameter \(S = 2^{2/3} V^{2/3} (k^{-2/3}+2k^{1/3})\)

For a cirucmscribed polygonal prism: \(S = (n \cdot sin(2π/n))^{1/3} (2V)^{2/3} (K^{-2/3} + sec(π/n) K^{1/3})\)

Graphing what this means for a nominal surface area:

Which suggests a surprisingly broad range where the surface area is “good enough”. At least with relatively dense propellants.

Actual Tankage and Propellants

JNO

Actual propellant densities may appear surprising, given the way tanks are idealized. This is because by default JNO assumes that only 55% of the volume can be used. This can be changed in settings, though the only default propellant that uses it is solid fuel (which uses 40%).

| Propellant | Theoretical Density (kg/m³) | Practical Density (kg/m³) |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Fuel | 1700 | 680 |

| Kerolox | 1020 | 561 |

| Hydrolox | 320 | 176 |

| Methalox | 790 | 434.5 |

| Hydrogen | 71 | 39.05 |

| Monopropellant | 1021 | 561.55 |

| Water | 1000 | 550 |

| Xenon | 1700 | 935 |

As mentioned before, tankage always has a surface area mass of 12.5 kg/m². Other parts may be different, and adding heat shielding will generally up the mass. This density range (especially the kerolox-hydrolox one) will trip a new person who isn’t comparing masses and is suddenly confused at why they’re getting less \(Δv\) with a higher \(I_{sp}\) propellant combination.

While I haven’t looked at it in any detail (hence the lack of example craft), these densities may still provide some surprises even when accounting for overall mass changes.

Things also get messy in terms of ultimate Δv limits at 0 TWR because of how bigger tanks are more efficient (so it’s to a degree about the largest tank and smallest engine).

KSP RSS/RO

Tanks have varying utilization fractions based on type (as well as varying surface masses). Propellants also vary greatly in density. That typed, empty mass scales directly with volume (so height vs diameter and large vs small does not matter). Given the large number of propellants (and how they are in an even larger number of combinations), they are largely glossed over. Tank volumes (for the most common types) do act as thin-walled cylinders of varying utilization fraction, though, so those are easily listed.

| Tank Type | utilization (%) | basemass (kg/l) | emptymass (kg/l) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Steel | 83 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| HP Conventional Steel | 75 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| Conventional Al | 87 | 0.03955 | 0.04 |

| HP Conventional Al | 84 | 0.13364 | 0.15 |

| Conventional Al2 | 92 | 0.027 | 0.027 |

| HP Conventional Al2 | 90 | 0.10761 | 0.12 |

| Conventional AlCu | 92 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| HP Conventional AlCu | 90 | 0.0804348 | 0.09 |

| Conventional AlLi | 97 | 0.0155 | 0.0155 |

| HP Conventional AlLi | 96 | 0.0445361 | 0.05 |

| Conventional Stir | 97 | 0.0145 | 0.0145 |

| HP Conventional Stir | 96 | 0.03959 | 0.042 |

| Conventional Starship | 97 | 0.018 | 0.018 |

| HP Conventional Starship | 96 | 0.05938 | 0.08 |

| Isogrid Al | 95 | 0.016 | 0.016 |

| HP Isogrid Al | 93 | 0.0509053 | 0.052 |

| Isogrid AlCu | 95 | 0.121 | 0.121 |

| HP Isogrid AlCu | 94 | 0.0465053 | 0.047 |

| Isogrid AlLi | 97 | 0.0115 | 0.0115 |

| HP Isogrid AlLi | 96 | 0.038598 | 0.039 |

| Isogrid Composite | 97 | 0.0095 | 0.0095 |

| HP Isogrid Composite | 96 | 0.028 | 0.028 |

| Isogrid magic | 97 | 0.0065 | 0.0065 |

| HP Isogrid Magic | 96 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Balloon SteelAl | 100† | 0.014 | 0.001 |

| Balloon SteelAlCu | 100† | 0.0115 | 0.001 |

| Balloon SteelAlLi | 100† | 0.01 | 0.001 |

†Minimum utilization fraction is 99% (while for other tanks there is no lower limit). This usually isn’t an issue for the sorts of things this post is optimizing for.

For a cylindrical tank, volume is \(πd^2h/4\), so with typical sizes (m), you’ll get a volume in kL. My numbers in the table reflect that and getting masses in tons, though a lot of propellant info in the game files will be for dealing with tons of mass and liters of volume. (hence the mass multipliers in the files being a factor of 1000 smaller. Conveniently kg/l is the same as ton/kl.)

The mass of a tank that is not configured for fuel is \(m = volume \cdot basemass\). One that is will be \(m = volume \cdot basemass + volume \cdot utilization \cdot defaultmass\). This often roughly doubles the tank mass.

MLI etc probably changes these numbers a bit. Avionics and the like are assumped to be part of the payload.

Propellant densities are not listed here, as they depend on the exact properties and ratios, and so very with different engines and variants of the same engine. There are far too many to enumerate, and it may make sense to note values (or overall mass ratios) in-game instead.

Fiddling with all those tank and fuel properties (and there are a lot of tanks, propellant types, and ratios) can be enough of a hassle that one might ‘just’ use the previous equation, and get the new value of R out of the VAB. eg:

\[T = volume \cdot (basemass + utilization \cdot defaultmass)\] \[RT = volume \cdot (basemass + utilization \cdot defaultmass + utilization \cdot ρ_{propellants})\]Two Stages (again)

The equation I derived last time was done fairly simply – ΔV for two stages, with a bunch of parameters fixed so you’re only moving tanks between the two stages. Then take the derivative of ΔV with respect to the fraction of tankage in the upper stage, and find where it equals 0. You can also do that when the stages have not just different Isps, but different mass ratios for the tankage:

Definitions

\(T\) Total (full) tankage

\(T_u\) Upper Stage (empty) tankage

\(R_u\) Upper stage tankage mass ratio (and this means that the full mass of the upper stage tankage is \(R_u \cdot T_u\)

\(R_l\) Lower stage tankage mass ratio

The lower stage tankage is not explicitly defined (so no \(T_l\)), but as \(T - R_u T_u\) when full and \((T - R_u T_u)/R_l\) when empty

\(E_l, E_u\) Lower and upper stage engine masses

\(S\) Staging separator/misc lower stage equipment. (eg: fins, and perhaps avionics)

\(P\) Payload (which also includes anything that isn’t really mission payload in the upper stage,but isn’t the propellant, tanks, or engines)

\(V_{l}, V_{u}\) Effective exhaust velocity for each stage

Derivation

\(Δv = V_{l} \cdot ln(\frac{E_l+T+S+E_u+P}{E_l+(T-R_u T_u)/R_l + S+E_u+R_u T_u+P}) + V_u \cdot ln(\frac{E_u + R_u T_u + P}{E_u + T_u + P})\)

\[\frac{\partial Δv}{\partial T_u} = V_l\frac{\frac{1}{R_l}-1}{E_l+\frac{1}{r_l}(T-R_uT_u)+S+E_u+R_uT_u+P} + V_u\frac{(R_u-1)(E_u+P)}{(E_u+T_u+P)(E_u+R_uR_uT_u+P)}\] \[0 = V_lR_u(\frac{1}{R_l}-1)(E_u+T_u+P)(E_u+R_uT_u+P) + V_u(R_u-1)(E_u+P)(E_l+\frac{1}{R_l}(T-R_uT_u)+S+E_u+R_uT_u+P)\]Collecting terms:

a \(T_u^2 = V_lR_u^2 (\frac{1}{r_l}-1) T_u^2\)

b \(T_u = [V_lR_u(\frac{1}{R_l}-1)(E_u+E_uR_u+PR_u+P) + V_u(R_u-1)(E_u+P)R_u(1-\frac{1}{R_l})] T_u\)

c \(= V_lR_u(\frac{1}{R_l}-1)(E_u+P)^2 + V_u(R_u-1)(E_u+P)(E_l+\frac{T}{R_l}+S+E_u+P)\)

\[T_u = \frac{-b±\sqrt{b²-4ac}}{2a}\]And if you have \(R_l = R_u\), this simplifies to what it was last time. (barring any errors on my part)

This presents the same situation as last time – you can constrain overall craft size by first stage TWR, but the need to have only one variable means you’re not optimizing for Δv rather than payload, and can’t extend this to 3+ stages. Control requirements very much risk complicating though, though. (Depending on where you put the avionics)

Given the limitations on how mass ratios can vary when suffling mass between stages (and possible shape constraints), something similar could probably be done for craft in JNO with enough effort.